Addressing India’s Water Crisis

The story of India’s water crisis today is not an accidental occurrence. What is unfolding in front of us has been warned by both experts and practitioners several times over the last decade. According to a report “Composite Water Management Index”, published by NITI Aayog in June 2018, India is undergoing the worst water crisis in its history and nearly 600 million people are facing high to extreme water stress. 21 major cities including Delhi, Bengaluru, Chennai, Hyderabad are racing to reach zero groundwater levels by 2020, affecting 100 million people.

The report further mentions that India is placed 120th amongst 122 countries in the water quality index, with nearly 70% of water being contaminated. While the government has formed a new ministry, the ministry of Jal Shakti that brings all water management under one umbrella to discuss, plan and do better water management, there is still a huge gap in a systematic approach for better management of this precious resource.

A Systems Approach to Alleviate Our Water Crisis

No complex problem can be solved with a simple, one dimensional solution. So, particularly, it is with water. Even so, it is useful to work on such issues through conceptual frameworks that are easily and widely understandable. Our experience in the field of water boils down to the three primary pillars of human endeavour: The people-nature issues (maintenance of the health and purity of water resources and sources); the people-practice/machine issues (tools, techniques and technologies for water conservation and management) and people-people interactions (institutions, behaviours and governance for water management)

While rural and urban situations require different management priorities, the principles remain the same.

- Understanding the water resource system in its entirety – the source (direct and indirect), flows (surface and subsurface), the demands, the distribution, governance and access issues, the efficiency of use and reuse. Assess the situation – drivers, pressures/demands, impacts and response strategies in place.

- Ensuring stakeholder participation and inclusion in the process of solution finding as well as in implementation and assessment (including monitoring) of results – this will require a shared understanding of the issues and expectations of potential impact of solutions from the conservation, management and polices perspectives.

- Look for solutions at the people-nature, people-practice, people-people and people-uses interfaces based on a principle of subsidiarity which identifies the level at which any solution should be optimally applied and managed. And, build capacities across all stakeholders for the roles they need to play.

It is important to recognise the inter-dependencies and the rural urban continuum with respect to water management and governance. The water demand patterns indicate over 70% in agriculture with varying levels for industry and urban and rural domestic and commercial use.

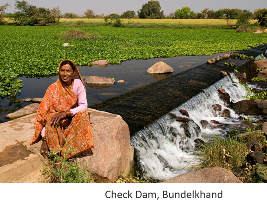

Our understanding of the semi-arid and rugged geography of Bundelkhand, the system of water use in agriculture and other applications, the socio-economic and cultural systems indicated that the solutions lay in a combination of land and water management techniques used for centuries in efficient and judicious use of water resources for irrigation, agriculture and allied activities, along with shifts in agriculture and livestock practice.

The regeneration of local water cycles by constructing water harvesting structures such as check dams, farm ponds, and reservoirs and revitalising village ponds through community action in collaboration with local and district governments brought life to rivers and streams that had, over the past few decades, virtually died and it also recharged the shallow and deep aquifers leading to improved ground water tables. This not only made water available in the wells for human and cattle consumption, it also enabled water for irrigating agriculture fields. Farms that would be left fallow for half the year were brought into production, and single cropping area converted into double and triple cropping in many villages.

Engagement with farmers groups for managing the land and water with the message “gaon ka pani gaon mein aur khet ka pani khet mein” and “more crop for every drop” brought in the systems for field bunding, line sowing, low tillage, micro-irrigation and shifting to crops that need less irrigation have enhanced water use efficiencies. In addition, farmers are also encouraged to adopt small agro-horti wadi model that gives them production security by diversifying their agriculture, enhanced soil moisture and provided greater resilience in drought years.

At the village level, water user societies, watershed committees and women’s self-help groups have taken charge of planning, implementation and management of the resources and infrastructure. They engage with their village panchayats for the governance of water resource systems at the village level. A case in point is the establishment and maintenance of piped drinking water systems in many of these villages which now run on energy from solar pumps, are regularly monitored for water quality and managed by women’s federation members who charge user fees and manage water distribution services across village customers.

At the settlement level, it is important to look at the water system holistically from source management to water treatment and recycling. Decentralised solutions for waste water management and recycling water back into use should be practiced so that fresh water demand can be reduced. The crisis is certainly not because there is no water. We have plenty of water, but we have failed to manage this valuable resource, year after year. To continue to reap the benefits of this valuable resource in a sustainable fashion, we must work towards integrated water management.

K Vijayalakshmi

kvijayalakshmi@devalt.org

The views expressed in the article are those of the author’s and not necessarily those of Development Alternatives.

This blog first appeared as an editorial in Development Alternatives Newsletter March, 2020

Leave a Reply